Venture Capital Fund Structure

De-mystifying the structure of a venture capital fund and how it works.

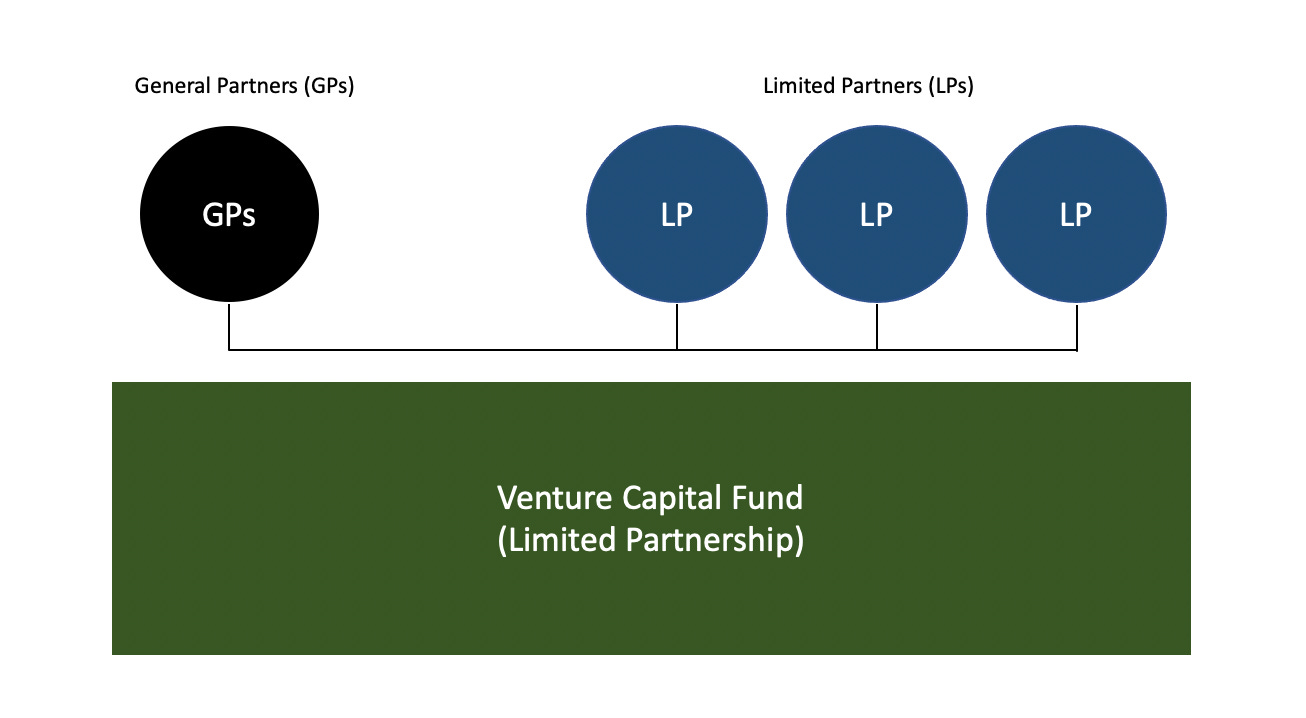

Like startups, venture capital funds need investors. A venture capital fund is a pool of capital raised from various investors to invest in startups with significant growth potential.

The structure of a venture capital fund varies based on factors such as the fund's strategy, size, and preferences of the fund manager, but there are common elements in their structure. Here is a breakdown of everything you need to know.

Key Players in a Venture Capital Fund

General Partner (GPs): The fund manager, or General Partner, is responsible for the active management of the fund. The GP usually has expertise in investing, startup operations, and industry knowledge. The GP makes investment decisions, manages the portfolio, and handles the day-to-day operations of the fund. GPs are liable for the fund.

GPs often put their own capital into the fund to demonstrate their commitment to the fund.

Limited Partners (LPs): Limited Partners are the investors who contribute capital to the fund. These can include institutional investors, high-net-worth individuals, family offices, endowments, and pension funds. LPs only provide capital for the fund and have a limited role in the fund's management decisions. LPs are only liable for the amount of their investment in the fund.

Fund Structure: Venture capital funds are typically structured as Limited Partnership Agreements. The fund manager, or GP, forms the partnership and manages the fund's operations, while the LPs contribute capital. The fund's lifespan is defined in the Partnership Agreement and is usually around 7-10 years, with the option to extend via fund recycling.

Single-member companies, which are most common for new GPs, are regarded as “disregarded entities” under U.S. tax code, while multi-member companies are treated as partnerships. In a Limited Partnership, there must be at least one GP.

Types of Fees in a Traditional Fund

Fund Organization and Administration Fee: Fund formation and administrative fees are fund expenses that are paid by the fund and allocated on a pro-rata basis. These types of fees include setting up the Limited Partnership, tax, legal, and other administrative items. Terms are defined in the Partnership Agreement.

Filing fees to register a limited partnership can cost anywhere from $500 to $2.5k annually. Then there are attorney fees to set up the fund, which can typically cost several thousand to tens of thousands of dollars depending on the complexity of the fund.

Once the fund is up and running, a GP is likely to pay ongoing legal fees related to side letter negotiations, amendments to the fund’s operative documents, and other expenses that require legal expertise. Additional fund administrative fees include the preparation of financial statements as well as annual tax preparation services.

Management Fee: The GPs earn annual management fees, which are usually a percentage (typically 2%, but may vary depending on the fund) of the committed capital from the LPs. These fees cover the operating costs of the fund, salaries, office expenses, and other administrative expenses. Management fees are charged every year in the fund’s operations. Terms are defined in the Partnership Agreement.

Seed funds sometimes charge higher management fees than later-stage funds because they have fewer capital commitments, and therefore may look for a proportionally larger fee to cover ongoing expenses.

A fund might also cap the amount of management fees it collects at a certain amount.

Management fees can be paid on a straight-line basis over the fund’s lifetime or be paid on a “step-down” basis in which a GP reduces management fees after a certain number of years or at the completion of a milestone (for example, when all investments are made).

Carry Interest: This functions as a performance bonus for the GPs when the fund produces returns. Carried interest is a percentage of the fund’s profits that goes to the GPs (typically 20%, but may vary depending on a GP’s track record and management fee). Terms are defined in the Partnership Agreement.

GPs receive their carried interest only after LP’s invested capital has been returned to them.

Carried interest may also be subject to hurdle rates (minimum returns a fund must make before carried interest can be paid out) or claw-back provisions (in which LPs can legally force the GPs to personally pay them back if the investments decline in value after the GPs have taken their carried interest payouts).

Negotiations Between LPs and GPs

Side letters: Agreements for certain rights, privileges, and obligations outside of the standard terms. LPs that request side letter agreements are typically seeking to minimize their downside risk or ensure that the fund is being operated in a way that meets their unique needs.

Lower Fees: Carry is typically 20%. However, some individual LPs may ask for a lower carried interest on their portion of the investment.

Greater Transferability Rights: LPs may ask to reduce restrictions surrounding their ability to transfer their stake in the fund to another party.

Enhanced Information and Reporting Rights: LPs may ask for more detailed or more frequent information and reporting than what the GP is required to provide to other LPs.

Excusal Rights: LPs may ask for the right to excuse their funds from being used for certain types of investments.

More Favorable Liquidity Terms: LPs may request distributions be paid out after each individual liquidity event.

Negotiating Fund Structure: GPs choose their own fee structures, but LPs can often negotiate a rate they feel comfortable with. Relevant questions for an LP to think about include:

What is the fund’s baseline carried interest rate?

How much has the GP invested in the fund?

Is carry paid on a deal-by-deal basis, or via overall portfolio returns?

Is there a step-down period for management fees?

Is there a clawback provision?

Will the side letter provision favor one LP at the expense of another?

Will the side letter provision be operationally feasible?